Difference Between Plant and Animal Cells: Key Features, Structure, and Functions Explained

Picture shrinking down to a microscopic world where every detail pulses with life. You’d find yourself surrounded by bustling cities inside tiny packages—some brimming with lush green factories, others humming with energy and movement. What makes these miniature universes so different? Why do some sparkle with emerald chloroplasts while others rely on a powerhouse called mitochondria?

Understanding the difference between plant and animal cells isn’t just a science class memory—it’s a key to unlocking the secrets of how life adapts, survives, and thrives. Once you see how these cells shape everything from the food you eat to the oxygen you breathe, you’ll appreciate the hidden choreography that keeps our world spinning. Ready to uncover what sets these cellular worlds apart? The answers might just surprise you.

Overview of Cells

Cells underpin all living things, acting as the smallest units of structured life (Alberts et al., 2015). You see them in plants, animals, fungi—everywhere you find life, you’ll find cells working together. They’re like the tiny architects that design every intricate detail, from roots in a forest to muscle fibers in your arm.

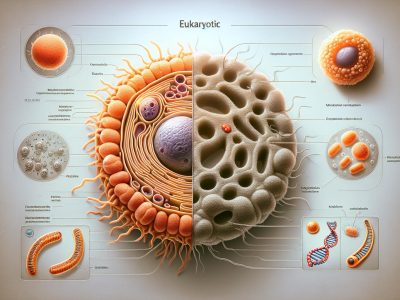

Cells come in two main types: prokaryotic, like bacteria, and eukaryotic, like plant and animal cells (National Institutes of Health). Prokaryotes lack a defined nucleus; they’re a bit like unorganized workshops. Eukaryotes, by contrast, have a nucleus enclosed in a membrane, which is almost like the security vault of a corporate headquarters. If you picture a bustling city, every eukaryotic cell is a skyscraper, its nucleus the central hub where all vital decisions get made.

Inside, cells contain organelles, each with its own job. For example, mitochondria generate energy, much like power plants supply electricity. Chloroplasts in plant cells act as solar panels, capturing sunlight for photosynthesis. Without these minuscule entities, neither grass in your backyard nor the steak on your plate could exist.

Cells communicate through chemical signals, forming tissues and organs. When you scrape your knee, immune cells rush in, repair systems activate, and within days, new skin forms—all coordinated by cell-to-cell talk (Molecular Biology of the Cell, Garland Science).

If you ever wondered how your skin knows how to heal or your favorite houseplant leans toward the sun, the answer sits in the specialized duties of plant and animal cells. Considering that trillions of cells orchestrate every blink, breath, or blossom, what overlooked details might you notice now? Each cell’s micro-world shapes life on a breathtaking scale.

Key Similarities Between Plant and Animal Cells

Both plant and animal cells share fundamental eukaryotic cell structures, forming the intricate base of your bodily system or the green tissues in your garden. Each cell comes with a nucleus, containing DNA, which’s like a command center storing blueprints—a story millions of years old. You and an oak tree both rely on this “executive office” to orchestrate critical life processes.

Cytoplasm fills both kinds of cells, a jelly-like substance where essential reactions unfolds. Picture cytoplasm as the bustling streets in a city, connecting various organelles—like mitochondria, which you might call the cell’s “powerhouses”. Every breath you take or meal you digest, mitochondria busily convert nutrients to energy, just like they do in the grass beneath your feet (Alberts et al., 2014).

Ribosomes exist as little factories, scattered and hard at work in both cells, building proteins from instructions in genetic material. Whether you’re flexing a muscle or a sunflower’s stem leans to sunlight, proteins get assembled in precisely the same way—by these microscopic technicians.

Plasma membranes surround every cell, managing the movement of water, nutrients, and signals in and out. This thin boundary’s a vigilant city wall, letting in friends and keeping out threats. You’ve probably heard of osmosis—when plant roots soak up rainwater or red blood cells maintain their shape, osmosis underpins the balance.

While some stories highlight the differences—like chloroplasts exclusive to plants or lysosomes dominating in animals—the similarities reveal a shared script. Both cells use endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus to transport and package molecules, reflecting a universal workflow across living things. Think about this: when scientists engineered glow-in-the-dark mice (by introducing jellyfish genes), it worked because of shared cellular language between plant, animal, and even marine life (Chalfie et al., 1994).

Ask yourself—if these cells share so much fundamental machinery, what more might humans and plants exchanged throughout evolution? That question continue fueling discoveries in medicine, agriculture, and biotechnology.

| Shared Organelle | Role | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleus | Stores DNA, controls activities | Both oak tree & you |

| Mitochondria | Produces energy | Muscle movement, root growth |

| Ribosomes | Synthesizes proteins | Healing wounds, leaf repair |

| Plasma membrane | Controls passage of substances | Water balance, nutrient intake |

| Endoplasmic Reticulum | Transports proteins/lipids | Hormone movement, enzyme secretion |

| Golgi apparatus | Packages/sorts proteins & molecules | Antibody release, sugar transport |

Recognizing these connections makes biology less of a dry recitation and more of a living narrative, bridging your story with that of every leaf, pet, or bite of food.

Major Differences Between Plant and Animal Cells

You encounter plant cells and animal cells daily, sometimes in ways you never even considered. A single leaf and a pet cat—they’re both rooms in the mansion of life, yet each follows a different blueprint hidden at the cellular level. Curiosity can turn ordinary objects around you into learning tools. Have you ever asked yourself why you can’t photosynthesize like a tree in the park? Let’s see why.

Cell Wall and Cell Membrane

Cell wall exists only in plant cells, providing rigidity, support, and shape much like the walls of a house keep it standing. For example, every apple slice holds its crisp because of cellulose-packed cell walls, which you won’t find in a steak or a ballooning frog. Animal cells hold only a plasma membrane, a flexible yet sturdy boundary that isn’t rigid—it lets animal tissues move and bend, such as a dog’s wagging tail or a goldfish’s fluttering fins (Alberts et al., “Molecular Biology of the Cell”). Cell membrane surrounds the protoplasm in both, controlling what enters and leaves, but only plants possess the extra brickwork of a tough cell wall.

Chloroplasts and Photosynthesis

Chloroplasts occur exclusively in plant cells, powering the process of photosynthesis. These green, pigment-filled organelles act as microscopic solar panels, converting sunlight into food. If you ever watched a plant grow on a windowsill, that’s chloroplasts at work. Animal cells lack both chloroplasts and chlorophyll, so dinner isn’t made from sunlight; it’s usually found by roaming, hunting, or shopping. Ask yourself: if animal cells had chloroplasts, could you grow your breakfast just by basking in the sun?

Vacuoles and Storage

Large central vacuole appears in most plant cells, serving as a massive storage unit for water, ions, and nutrients. Ever noticed how a wilted lettuce leaf perks up after a quick bath? That’s the vacuole refilling and pushing the cell wall back into shape. Animal cells only sometimes form small, temporary vacuoles, which don’t store as much or help maintain structure. These tiny sacs in animals handle digestion or waste more like quick trash bins than the plant cell’s walk-in pantry (Cooper, “The Cell: A Molecular Approach”).

Shape and Structure

Typically, plant cells show a rigid, rectangular structure, their shape dictates how leaves stack and how roots dig. Probably animal cells, freed from stiff walls, mold into a variety of forms—spherical blood cells, branching neurons, or flat skin cells. That flexibility lets animals move and respond quickly, while plants stay rooted and stable. Picture a forest scene: each leaf’s tile pattern comes from plant cell walls, while creatures scurrying display animal cells’ supple structure.

Modes of Nutrition

Plant cells, equipped with chloroplasts, synthesize their own food through photosynthesis—autotrophic nutrition. This means every blade of grass is a tiny chef, crafting sugars from sunlight, carbon dioxide, and water (Taiz & Zeiger, “Plant Physiology”). Animal cells rely on heterotrophic nutrition, finding and consuming pre-made organic molecules because they lack the cellular tools for sunlight-powered food. While a cactus grows quietly in the desert, a wolf must roam, seek, and eat—making each meal a quest rather than a chemical reaction.

| Feature | Plant Cells | Animal Cells |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Wall | Present (cellulose) | Absent |

| Chloroplasts | Present (photosynthesis) | Absent |

| Vacuole | Large central vacuole | Small/temporary vacuoles |

| Shape | Regular, rectangular | Varied, flexible |

| Nutrition | Autotrophic (photosynthetic) | Heterotrophic (ingestive) |

Importance of Understanding the Difference Between Plant and Animal Cells

Grasping how plant and animal cells diverge shapes your view of biology’s grand story. You step into a lab, peer through a microscope, and gaze at two slides—one brimming with green brick-like structures, the other dotted with soft-edged blobs. Like two languages with their own rules, each cell type scripts the behaviors of entire kingdoms. For instance, plant cells come equipped with chloroplasts—tiny solar panels (think the lush leaves of a tall oak)—which let plants transform sunlight into sugars. Without animal cells, who gather energy by munching on those sugars, food chains would crumble. How bizarre would it be if you, a human, built your lunch the way grass does?

Recognizing these distinctions matters well beyond textbooks. If a botanist in a rainforest can’t tell plant cells from animal, rare medicines like vincristine—derived from a Madagascar periwinkle—might go undiscovered. Doctors rely on knowledge of animal cell function to target cancer’s rapid cell division (Alberts et al., Molecular Biology of the Cell, 2022). Farmers tweaking plants for drought resistance need insight into vacuole size and cellulose strength, or their crops wilt under summer sun. Even conservationists examining elephant diets must appreciate that animal cells can’t photosynthesize—meaning every bite connects to a photosynthetic origin.

Let yourself consider the strangeness of a world where all cells are alike—no luscious green forests, no grazing herds, no crisp lettuce on your plate. The difference isn’t just technical; it’s ecological poetry, every element—like mitochondria, cell walls, and chloroplasts—contributing to life’s chorus.

Could you picture your heart pulsing like a plant’s stem? Ask yourself why animal cells have flexible membranes while plant cells stick to their rigid frame. Each trait unlocked an evolutionary puzzle, letting moss live on rocks or a rabbit dash across fields. When you explore these distinctions, you’re not memorizing trivia—you’re decoding the legacy of adaptation.

If you question why spinach leaves survive a frost or why muscles move, the answer hinges on these microscopic divides. Your daily breath flows from a conduit beginning in a plant cell’s chloroplast, ending in your lungs. In every science classroom or wild meadow, this knowledge translates into respect for life’s ingenuity.

Grappling with these differences shapes your judgment as a citizen, a patient, a steward of Earth; it answers not just “what,” but “why” the world thrives in infinite shades of green, fur, and flesh.

Conclusion

When you take a closer look at plant and animal cells, you’re stepping into a world of remarkable complexity and purpose. Every detail, from the structure of their membranes to the way they generate energy, reveals how life has adapted to thrive in different environments.

By deepening your understanding of these cells, you open up new ways to connect with the natural world. Your curiosity can drive discoveries that shape the future of science, agriculture, and conservation, reminding you that even at the smallest level, life is full of wonder and possibility.

- Alternatives To ClickTime - December 28, 2025

- Comparing the Nutritional Value of Almonds and Walnuts - December 28, 2025

- Comparative Nutritional Analysis of Red and Green Cabbage - December 28, 2025